Data has been the new buzzword for a few years now; there are 2.5 Quintillion bytes of data created each day at our current pace (Forbes). I don’t know what a Quintillion is, but I’m positive it’s beyond what my mind can fathom.

What data are you using to measure your performance, and how do you know this data isn’t a vanity metric and is actually valuable to your business?

The biggest thing to keep in mind is that no specific value is always a vanity metric; rather, the “vanity” term applies when numbers are provided out of context or do not serve a direct measurement purpose. A good way to sniff out vanity metrics is to ask: is this number just something that sounds “cool” to pass up to management? Or does it provide insight that helps make day-to-day decisions?

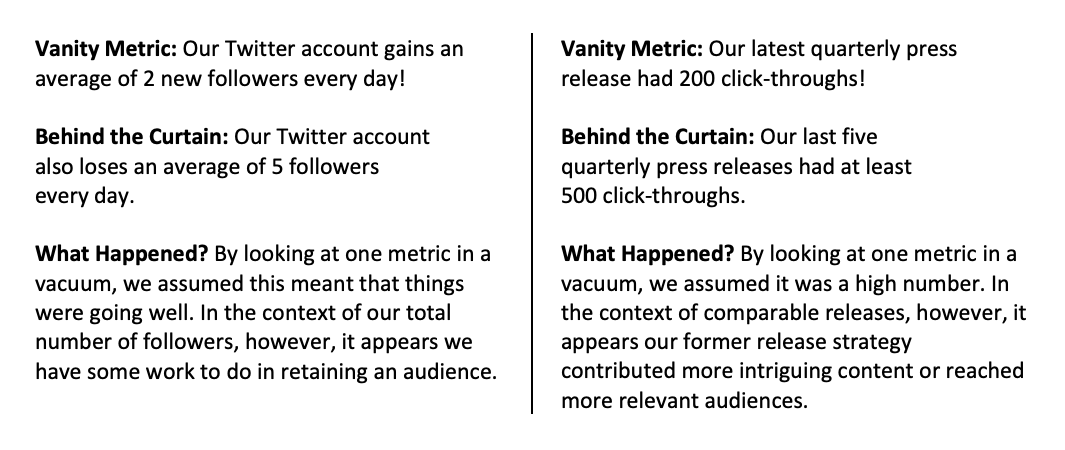

Let’s take a look at some basic examples before diving into ways you can avoid these mistakes.

Both vanity metrics above are standalone numbers that somebody has shown their boss, guaranteed. Once we pull back the curtain it gives the vanity metric context and provides clear next steps on how to take action to improve the results. This is what we want!

In PR, the “vanity” label is typically slapped onto values such as UVPM or AVE. If those are the only metrics your PR team is using, I agree entirely. We are no longer living in a world restricted to newspapers and billboards where a very rough guess at views is acceptable. Everything is digital – everything – even refrigerators and toothbrushes are tracking consumer data. So why is PR allowed to run blind and pretend that real metrics don’t exist?

Consider UVPM (Unique Visitors Per Month). UVPM is measured at the outlet level and provides the number of visitors that outlet, as a whole, receives per month. PR historically adds up UVPM numbers from any outlet they were mentioned in and calls this their audience. I call that silly.

Let’s say I was mentioned in Ad Age, the Pittsburgh Business Times, and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Ad Age: 3.17M UVPM

Pgh Business Times: 3.37M UVPM

Pgh Post-Gazette: 4.77M UVPM

Total UVPM: 11.31M !!!!!

But wait, isn’t Pittsburgh’s entire metro population only 2.36M? Even New York City’s population is 8.62M. More people read my specific article than live in southwestern PA and NYC combined?! (Nope.)

Two blatant factors need to be considered with UVPM:

- Just because your article appeared in an outlet doesn’t mean every unique visitor per month has read it. Ad Age may have over 3 million people visit their site per month but how many of those read your specific article?

- These numbers are not deduplicated across outlets when combined. The odds that someone living in Pittsburgh has visited both the Pittsburgh Business Times and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in a full month’s time frame are, let’s face it, pretty high. Adding these two statistics without the ability to identify individuals and determine overlap is highly inflating the numbers.

While I may have been mentioned in all three publications above, I cannot genuinely claim that over 11 million people saw my brand’s name. That number, however, could be my very top of funnel metric, which I’d call “potential reach” and append with many more metrics down the funnel.

Now consider AVE (Advertising Value Equivalent). AVE is an attempt to quantify PR as if it got the spend of a paid advertisement, typically incorporating coverage, placement, and even credibility. I appreciate the attempt – PR and Comms teams should absolutely be able to quantify their coverage and justify the dollar value it aligns with. However, AVE is not a hard statistic by any means, and is a very poor standalone metric.

There is no concrete way to measure AVE. In fact, as of 2017, many organizations including AMEC and CIPR have banned the use of AVE as a valid metric. Most calculations utilize ratios that compare Paid Media spend/size/reach to Earned Media spend/size/reach, with random multipliers thrown in there. (Sounds legit, right?)

Two blatant factors need to be considered with AVE:

- The content itself is not comparable. A small paid ad, let’s say two square inches on a screen, is jam-packed with value statements, logos, etc. to promote your brand. An article, however, spans an average of 12 square inches on a screen, and how often is your brand mentioned throughout? Also, what if it’s mentioned in a negative tone or amongst competitors?

- Earned Media is much more credible than Paid Media. If it is indeed a positive article about your brand, it comes across to consumers very differently than a paid banner advertisement would, for example. (Keep reading for more on this.)

AVE as it exists today should be avoided. However, moving the PR industry forward from a metrics standpoint is something I can definitely stand behind. Keep reading on how Cision integrates into the Paid Media space to gather validated insights, not vanity metrics, that can help PR teams begin to provide the same data that Paid Media has for a decade.

In short, when determining which metrics to use, ask yourself: Does this give me insight into the individuals I’ve truly reached with my PR? Am I confident it represents the value in my efforts? Are there actually insights I’ve gained from these metrics that will drive tomorrow’s decision making?

Now that it’s clear what Vanity Metrics are, how can PR and Comms act on this knowledge? Look for part two of this three part series in the coming weeks.